Many visitors come to Long Island Aquarium to learn about aquatic and marine life from around the world. But what most visitors do not see is the enormous amount of work that goes on behind the scenes. In addition to caring for the animals and building, operating the facility, and maintaining the elaborate life support systems, our animal care staff is also involved in a variety of research projects. Our research helps us to better understand the organisms with which we work, and the data generated can be invaluable to conservation efforts. Some of our staff have traveled the world to present their research at various conferences. Besides managing our own in-house projects, we have also assisted many researchers and graduate students with projects they are working on.

Partner Projects

Current

Long Island Aquarium staff members often participate in research projects conducted in partnership with professionals from other leading institutions. These projects play a vital role in expanding our knowledge of particular marine species.

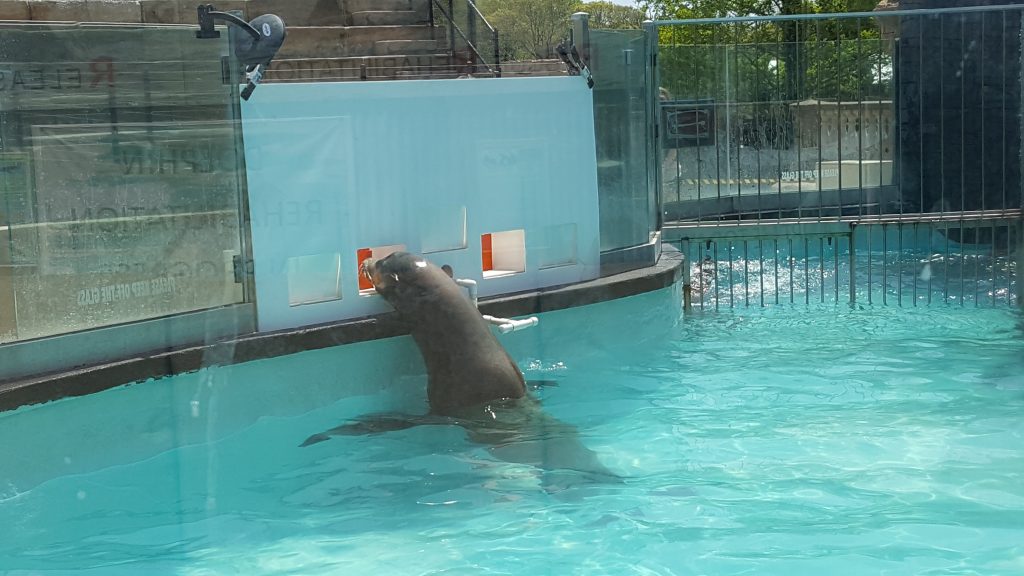

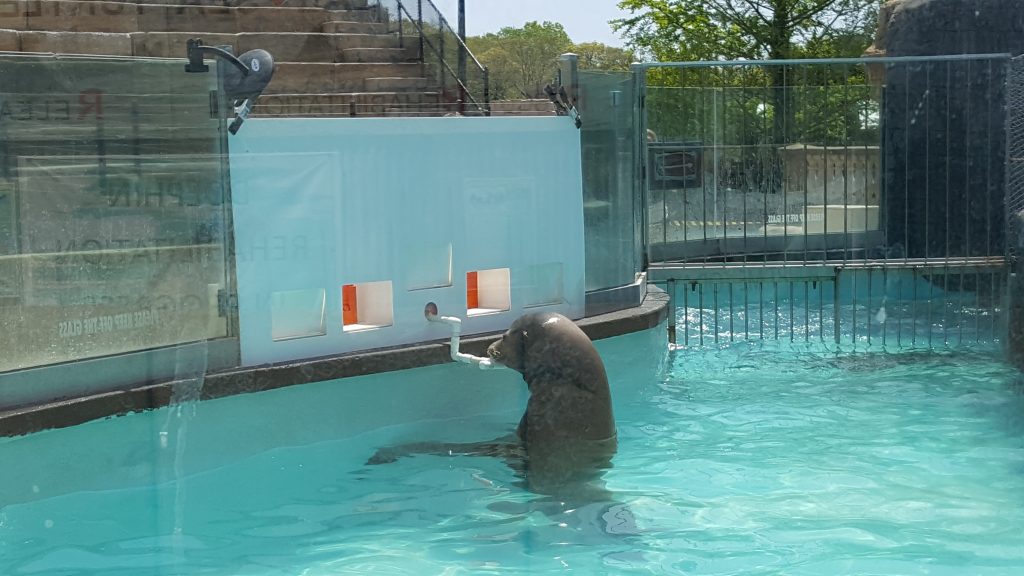

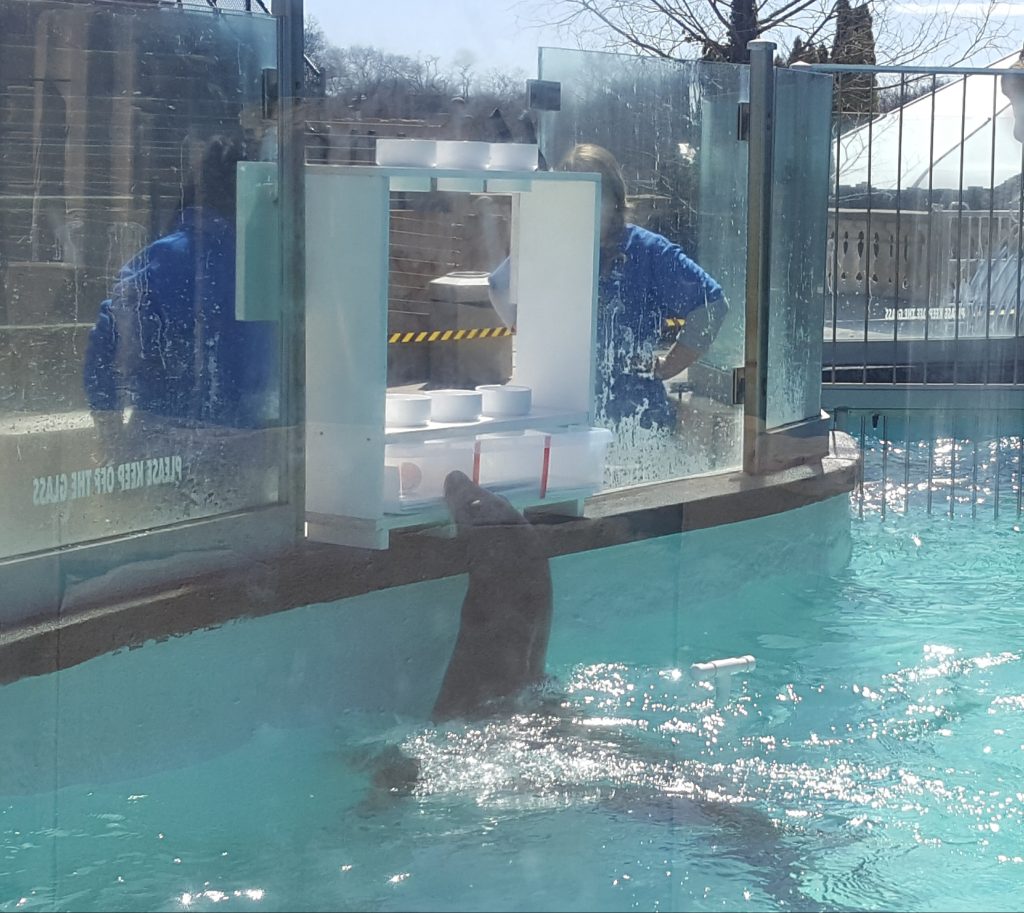

The following is a brief description of the specific research that we are currently working on with Dr. Kristy Biolsi and Dr. Kevin Woo. We work with them on various projects in the areas of cognition/problem solving and education/conservation. For example, our two adult sea lions are involved in a study on discrimination learning and symbolic representation, our adult female sea lion and one of our adult female harbor seals are involved in a cognitive study on the gravity bias (investigating naive physics among other theories), undergraduates use web-cams to learn about conducting non-obtrusive studies on animal behavior, and we allow access for hydrophone and video recordings in the seal and sea lion habitats to help with research on ambient noise levels on marine mammal behavior. In addition to these various areas of research, we work with C-SPEC and their affiliates on education and conservation through participation and presentations at public events held at St. Francis College. All above mentioned research has been presented at scientific conferences and/or published in peer-reviewed/scientific journals. In addition, there are a number of future projects in preparation.

1. Object to picture transfer

This work is being carried out with two trained California sea lions (Java and Bunker) at the Long Island Aquarium (LIA). The primary objective of this research is to study the process of learning, and in particular how physical objects in the world are mentally represented. Many objects in the world are represented in different ways, such as through symbols (e.g., language – both written and verbal/gestural), and pictures/photographs. How one transforms a stimulus from the physical world into a mental representation and how we can use multiple items with varying physical properties to represent the same item has been an enduring and expanding area of interest in many scientific fields. The question of whether these transformations are learned over time, or if it is an automatic cognitive process, does not currently have an adequate answer. The process appears to be effortless but often in science we find that the processes that occur most easily to us are in fact the most complicated.

Our research in this area is adding to the current knowledge base on concept learning and object representation by investigating how non-humans represent stimuli across different mediums. A secondary research goal is to not only understand the mental process by which these transformations may occur, but to integrate this knowledge into a better understanding of how these animals function in the wild and to therefore gain a better understanding of behavioral ecology in relation to this species.

2. Ambient noise study

We are collecting data using a hydrophone and a GoPro to evaluate the noise levels in the pinniped habitats at both the LIA and the Maritime Aquarium in Norwalk CT. This work consists of various analyses of the seals’ behavior in connection to the noise levels in the seals’ habitats at the LIA. Hydrophones and a Go-Pro camera are being utilized to correlate ambient (background) noise levels in the underwater habitats for the seals and sea lions at two aquariums with any potential changes in animal behavior as well as a monitoring of overall noise levels related to time of day at these facilities.

The current study seeks to add to previously obtained data by recording baseline noise levels and animal behavior on exhibit.

3. Web-cams at the LIA

Four C-SPEC web-cams have been placed at the LIA which allow for remote observation of exhibits. Researchers and approved RA’s are able to access and control video feed, and record, 24 hours a day/seven days a week in exhibits for the (1) Japanese macaque monkeys, (2) Atlantic harbor seals/gray seal, (3) California sea lions, and (4) river otters.

The cameras can be utilized for a number of reasons and RA’s are encouraged to propose research questions and studies that can be conducted using passive observation through the camera set-up. Camera access is granted by Director/Assistant Director permission only. Anyone who has access to the camera system MUST return the camera position to its original location (zoomed out) as these are also used by the LIA security team.

Example of projects possible with web-cam setup:

- Ethograms/Activity budgets

- Enrichment studies

- Inter/Intra-species interactions

4. Gravity Bias

This study was initiated, and primarily run, by SFC psychology MA student Afia Azaah during the 2016-2017 academic year. To date, of the various species tested (including developing humans under the age of two years), most subjects fail a task of logic and demonstrate what is known as the gravity bias. C-SPEC is working to investigate this in seals and sea lions both on land and under the water. It is the first test of marine mammals of any kind as well as the first test of an amphibious animal. This is interesting to study as amphibious species (such as seals and sea lions) encounter the effects of gravity on both land and under the water where some objects sink and others are buoyant.

- M. Hood defines a gravity bias as an effect that happens when “preschool children expect a falling object to travel in a straight line even when there are clear physical mechanisms that deviate the object’s path”,(Hood, Houser, Anderson, & Santos, 2001, p. 35 ). The gravity bias has been demonstrated with various nonhuman animal species such as the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) (Tomonaga, Imura, Mizuno, & Tanaka, 2007), gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), bonobo (Pan paniscus) (Cacchione, Call, &Zingg, 2009), rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) (Southgate & Gomez, 2006),the domesticated dog (Canis lupus familiaris) (Osthaus, Slater, & Lea, 2003) and in very young children (Hood, 1995; Joh, Jaswal, & Keen, 2011). This seems to be a developmentally based cognitive skill in humans with emergence around 2-4 years old (Hood, 1995). Investigating the gravity bias in amphibious mammals such as seals and sea lions adds to the growing research on this task across mammalian species and allows for a larger set of comparative data therefore providing a better understanding of the underlying cognitive mechanisms.

Completed

Seasonal Movements of Sand Tiger Sharks (Carcharias taurus) in the Western Atlantic Ocean

Partnered with Hans Walters/Wildlife Conservation Society/New York Aquarium.

Description

The goal of this project is to clarify the seasonal movement patterns of sand tiger sharks in the western Atlantic Ocean. Since December 2000, 23 sharks have been tagged and released with Pop-Up Archival Electronic Transmitters off of the coasts of New York, New Jersey, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

Sand Tiger Tracking Program

The study of the movements of juvenile sharks which are found in local New York waters in the late spring/early summer is a crucial component of this project. From 2001-2003, Long Island Aquarium donated surplus juvenile sand tigers purchased from local fishermen, as well as vessels and crew to release tagged specimens back into the ocean. Long Island Aquarium has offered to continue their support in the tagging efforts for juvenile sharks.

Carcharias taurus is a depleted and protected species that migrates through waters governed by various state laws, which sometimes differ from federal law. Sand tigers, like many other large Atlantic coastal sharks, may also move across international boundaries. This ongoing study will provide an understanding of the marine habitats occupied by C. taurus at various times of the year. Such bio-geographical information is critical in order to determine where the species is most vulnerable to depletion from over-fishing or habitat destruction. This knowledge will enable the development of better and more consistent conservation strategies for sand tiger sharks in the western Atlantic Ocean. With increasing concern over the instability of shark populations worldwide, the success of this project will encourage the use of satellite telemetry in conservation-related studies of other potentially depleted shark species.

Studying the Biology of Chain Catsharks (Scyliorhinus retifer)

Description

The study of the biology of a deep sea shark, the chain catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer), that inhabits the continental shelf and slope (at depths of 100-400 meters) from Nova Scotia to Nicaragua.

Deep Sea Catshark Research

The studies currently underway include:

Partnered with Dr. John Morrissey, Ph.D/Hofstra University.

- The biggest myth in shark science is that sharks can be identified using their teeth or scales. The truth is, however, that teeth and scale morphology changes with location within the mouth or on the body, and with time (i.e., juvenile teeth/scales are shaped differently from those of adults). We use Scanning Electron Microscopy to examine the teeth and scales of male and female chain catsharks of all ages to show that tooth and scale morphology are too variable to provide useful taxonomic information.

- The diet of this small shark is virtually unknown. The stomach contents of catsharks that are landed as by-catch in local commercial fisheries are examined to determine their prey preferences in their natural habitat.

- An in-house colony of more than 100 chain catsharks is maintained to dispel another myth that sharks are insatiable predators. We are determining exactly how much food each individual consumes each day. Then, by comparing their daily intake to their weight gain, we will determine their assimilation efficiency, and consider if this important aspect of metabolism is affected by sex of shark, age of shark, or water temperature.

- Our catshark colony also enables study of various aspects of the reproduction, development and growth of these egg-laying sharks. By monitoring the members of our colony closely, we will determine number of eggs deposited by each female, interval between batches of eggs from one female, gestation time for the eggs, developmental sequence for the embryos within the egg case, size of young at time of hatching, growth rate of hatchlings, age at maturity and size at maturity. Moreover, by taking small blood samples, highlights of the above reproductive cycle can be correlated with concentrations of sexual hormones in the plasma of both sexes. Finally, because female catsharks store sperm for up to three years after mating, we can use genetic techniques to determine the paternity of their young. Are all of a female’s pups fathered by just one male? If they are fathered by more than one male, is it random or does the sperm from one male out-compete the sperm from other males to fertilize a disproportionate number of her eggs?

Feeding Kinematics in the Chain Catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer)

Partnered with Matt Ajemian/Hofstra University.

Abstract

Past studies of feeding kinematics in the elasmobranchs (sharks, skates, and rays) have focused on easily accessible species inhabiting the inshore and epipelagic portions of the ocean. Thus, our knowledge of feeding behavior in deep-sea elasmobranch fishes is nonexistent.

The chain catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer) is a member of one of the most well researched groups of elasmobranchs (order: Carcharhiniformes), yet its feeding strategies are unknown due to its inaccessible deepwater environment (>200m).

To better understand the feeding biology of S. retifer, we utilized high-speed videography to document the kinematic events during capture of two sizes of fish prey. Frame-by-frame analysis of the feeding behavior indicated that the chain catshark utilized stereotypical kinematics to capture its prey. In addition, prey capture was suction-dominated, which is in contrast to its taxonomic grouping among several ram-feeding sharks. Nonetheless, prey capture shows a strong similarity to the basic pattern of kinematic events described in feeding studies of other carcharhinoid sharks; although ram-suction indices were noticeably different from a closely related species (Cephaloscyllium ventriosum) previously studied. The suction-dominant feeding behavior of S. retiferappears concomitant with the feeding behavior of most benthic sharks.

Aquarium Projects

Current

The Long Island Aquarium staff is always working to further our understanding of the animals under our care, and to enhance their conservation.

Here’s your opportunity to learn more about current research projects at the Aquarium.

Aquarium Behind-the-Scenes Aquaculture Program

Besides keeping world-class Aquarium exhibits, Long Island Aquarium has an extensive behind-the-scenes aquaculture program.

Why is Aquaculture Important?

All around the world, populations of various marine organisms are in decline and in danger of extinction. There are a number of reasons, including pollution, overfishing, and habitat destruction, to name just a few. Every year, it is becoming more difficult to meet the demands of human consumers. Aquaculture provides a source for many of these animals and plants without having to remove them from the wild. Fish farms also help to contribute to local economies by providing jobs (in some cases, for displaced fishermen).

What Types of Animals does Long Island Aquarium Raise?

One group of animals that we focus on is corals. Our coral reef exhibit is one of the largest of its kind; a 20,000-gallon closed system. From this system we do a lot of coral propagation. As the corals grow, we take clippings from them. These clippings, or “frags,†are then transplanted into specially designed troughs. These troughs are shallow, with a lot of light and current. These conditions enable the corals to grow rapidly–up to a millimeter each day, in some cases. The coral frags are kept in the troughs until they are large enough to either transplant into a display tank, or to be traded to another Aquarium or a university.

But corals are just one group of animals that we raise. We have also successfully raised many species of both marine and freshwater fishes and invertebrates. Below is a partial list of such organisms.

Fish:

- False Clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris)

- Clark’s Clownfish (A. clarkii)

- Saddleback Clownfish (A. polymnus)

- Maldives Clownfish (A. nigripes)

- Maroon Clownfish (Premnas biaculteatus)

- Neon Goby (Elacatinus oceanops)

- Yellow-line Goby (E. figaro)

- Broad Stripe Goby (E. prochilos)

- Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus)

- Long Snout Seahorse (H. reidi)

- Dwarf Seahorse (H. zosterae)

- White Spotted Bamboo Shark (Chilosyllium plagiosum)

- Motoro Stingray (Potamotrygon motoro)

Invertebrates:

- Peppermint Shrimp (Lysmata wurdemanni)

- Shore Shrimp (Palaemonetes vulgari)

- Nudibranchs (Berghia verrucicornis)

- Moon Jelly (Aurelia aurita)

- Lagoon Jelly (Mastigias sp)

Our aquaculture research generates information that enhances our understanding of the biology and ecology of the organisms we raise. It also helps to advance the worldwide state of aquaculture. By sharing what we learn through articles and public presentations, we help benefit aquarists and aquaculturists around the world.

Presentations Given at Conferences by LIA Staff:

The Beauty of Training: The Story of Gray Beauty a Rescued, Blind Gray Seal

Abstract

Candy Paparo, Senior Marine Mammal Trainer, attended the 33rd Annual International Marine Animal Trainers Association (IMATA) Conference in November 2005.

Trainers from around the world gathered at the conference and gave presentations on a variety of topics, ranging from new husbandry procedures and health issues to the implementation of solutions to daily challenges and new customer interactive programs.

“I was excited to attend two seminars before and after the conference,” Candy said. They were given by Ken Ramirez, who is the director of training and husbandry at Shedd Aquarium in Chicago. Candy also gave a poster presentation on Gray Beauty; the rescued, blind gray seal that shares the true seal exhibit with the harbor seals at the Aquarium entrance. This poster showed some of Candy’s training experiences and successes working with Gray Beauty.

Candy explains “It’s great to attend such worthwhile conferences. Just having a forum for Marine Mammal Trainers to gather and help better manage and care for the animals with which we all work is important.”

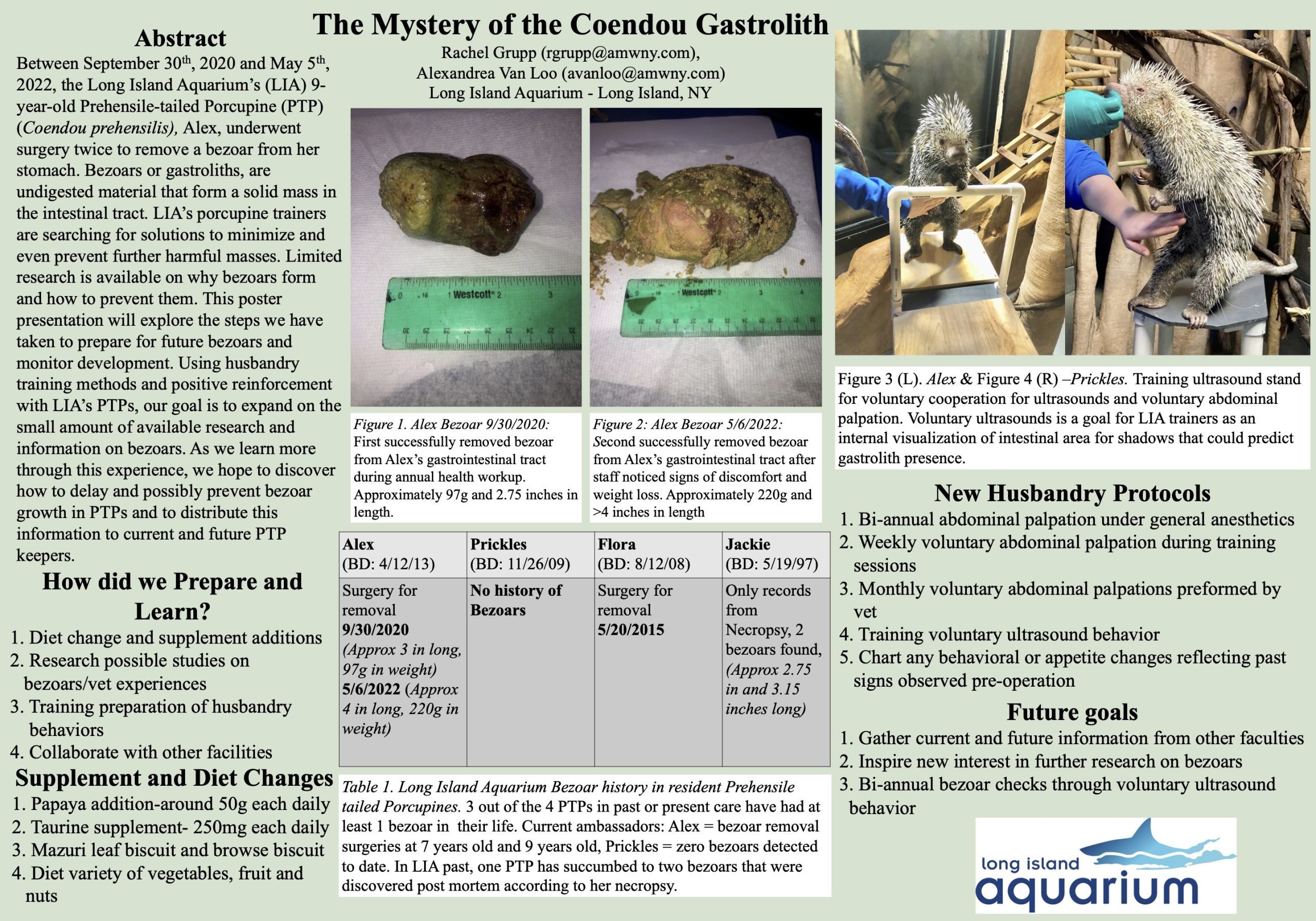

Porcupine Presentation

The poster presented focused on a medical instance that Prehensile tailed porcupines can acquire. The bezoar (or gastrolith) is a solid mass of undigested food material that can form and grow to large sizes within the porcupines stomach. Ultimately if not detected, the bezoar can rupture nearby organs and cause the demise of the individual. There is not much research done or known as to why some individuals lack the ability to break down certain foods to the point that it gathers within the stomach. Since discovering two bezoars during separate instances in our younger PTP, Alex, it is our goal and hopes to help bring attention to the matter and be in search of finding some answers or common ways to help prevent or even monitor the possibility of bezoars developing in any of our residential PTP.

During the poster presentation we were able to chat with other PTP trainers and keepers about the subject, learning helpful tips about husbandry training for monitoring their behavior as well as different diet additives that could help to break down or slow down bezoar formation. We were even able to help educate some people about the issue of bezoar possibilities in PTP who may have not known it was a threat or possibility.